Immortality: the state of having an infinite life span (in a living being) or being imperishable (in other sorts of entities).

1) Immortality is an element of faith in most religions, where commonly it is believed both that the worshipped god is immortal and that the souls of the faithful will be rewarded with immortality after their death. A remarkable exception is Japanese Shintoism, which is a religion without immortality.

2) Metaphorical immortality: This is the fame or notoriety of a person ("the immortal Schiller") lasting beyond her death due to such things as outstanding achievement in poetry, music or painting, the establishment of charity foundations, the production of descendants, the founding of a religion, or the performance of massacres or other atrocities. Scientists may obtain immortality in this sense by having ►natural constants, ►laws of nature or moon craters named after them.

3) Biological immortality, such as is found in protozoa and in simple multi-cellular forms of life: Invertebrate marine animals (echinoderms) such as starfish and sea urchins do not biologically age and have therefore outlived many generations of scientists in research aquariums.* Strictly speaking, such creatures at most deserve to be called potentially immortal, since biological degeneration is but one way of dying. Given an infinite amount of time, even they are certain of dying in some other way (such as from catastrophic changes in their environments due to human activity, to name one all-too-real possibility) sooner or later.

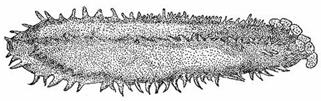

Immortal creature: stichopus chloronotus

One example of such potentially immortal creatures is the sea cucumber (stichopus), a sea dweller with a cylindrical body of up to 40 meters (depending on the breed), which you will often encounter while diving or snorkeling at the seafloor. Sea cucumbers, however, usually die of non-natural causes at some point; in Asia, pickled sea cucumbers are regarded as a delicacy.

4) Potentially infinite human life span by elimination of the aging process: The limitation of our lives is in radical opposition to our ►unlimited inner world of thoughts. It is an opposition once described by the novelist Nabokov as the "most radical humiliation, mockery and horror, to have developed within a finite span of life an infinitude of perception and thought". The meanness of this condition lies not only in the fact that we have to die relatively soon, but that on top of that our knowledge of this predicament hovers over us throughout our limited lifespan. It imposes a time pressure on everything we plan and do. Too many decisions that we make in the course of our lives cannot be reversed.

The hero of the very first epic that has been preserved in history, the Gilgamesh epic, strives for physical immortality. Literary examples of immortal humans are the mythical figure of Ahasver — the "eternal Jew" — as well as widely known characters such as ►Connor McLeod, ►Perry Rhodan, and ►Enoch Root. Less well known is Dr. James Bedford, who was the first to undergo the ►cryonic procedure in 1967 and hence is clearly ahead of the rest of us in the race for immortality.

Becoming Immortal by Not Aging

Gerontology is the scientific discipline dealing with the possibility of retarding or preventing the aging process. Body cells can fully regenerate through cell division, so that human biological immortality is possible in principle. Unfortunately, there are still some practical problems. Cells age due to damage to their proteins triggered by oxidants such as free oxygen radicals. These also cause erosion of the genes due to DNA copying errors during cell division processes. Moreover, each cell has its own "biological clock" — a kind of genetic self-destruct program that limits the number of cell divisions to around 50.

This clock ticks in the telomeres, which are the small terminals of the chromosomes inside the cell. They become increasingly shorter in rough proportion to the number of times the cell has divided. The shorter the telomeres are, the more divisions the cell has undergone. Below a certain telomere size, the division rate of the aging cell slows down. Eventually, the cell ceases to divide and dies. How long this takes depends on the type of cell, which is why we do not wake up one morning suddenly grizzled and toothless but age gradually, cell by cell.

Theoretically, the telomere shortening, and thus the process of aging, could be stopped, since telomeres can be fully regenerated by means of the cell nucleus enzyme telomerase. However, the aging process of the cells also provides protection against the unrestricted multiplication of malignant cells — cancer cells. Thus, before we can turn off the inner clock of a cell, we have to find a way to reduce the cell's vulnerability to cancer and DNA-copying errors. One way of achieving this involves the introduction of antioxidant-producing genes into the Mitochondria.

Some body organs such as the brain and eyes usually do not, by themselves, produce any new cells, though recent research has shown that even new brain and other neural cells are generated under certain circumstances — a process that is called neuronogenesis. These are very durable organs; if the rest of the body supported it, the brain, for example, could have a life span of 800 years. Nonetheless, aging is a complex process affecting many organs in different ways and is therefore hard to stop or reverse. This is probably one of the reasons why evolution has not yet designed any higher biologically immortal forms of life. To render human beings biologically immortal, it would not suffice to prescribe a pill; you'd have to radically change our biological make-up. The following improvements, at least, would be needed:

► The brain would require a new system of protein folding as well as enzymes to destroy defective protein chains, thereby preventing neurodegenerative old-age diseases.

► The permanent growth of teeth, common in horses, for example, would need to be achieved, a development that could put dentists and denture manufacturers out of work — though perhaps a new class of highly-trained professional tooth-filers would spring up in their place.

► A third, transparent eyelid, which opens in the dark, would prevent the intrusion of UV rays into the eye, thereby preventing most old-age vitreous and retina problems.

► A teflon-like inner coating of the blood vessels would relieve the heart and prevent blood vessel calcification.

► New growth factors would have to be introduced to provide for permanent regeneration of the bone substance.

Looking far ahead into the future, some exotic methods to obtain immortality may consist in implanting nano machines to permanently repair defective body cells or to transfer human consciousness into the memory of a computer network.

When Do You Want to Die?

Optimistic scientists such as the biologist Aubrey de Grey and the futurologist ►Ray Kurzweil hope for a breakthrough regarding biological immortality by the year 2030, while more pessimistic ones do not expect it to take place before around 2200. Certainly, it will also depend on the availability of financing for gerontological research and thus on the significance humankind assigns to the possibility of immortality. But is it desirable at all to stop the aging process? Or, in other words, isn't decay and subsequent death preferable? Notably, of 200 participants in an ►online poll conducted through this website 39% desire to obtain an unlimited lifespan. 46% wish to reach an age of up to 500 million years, and only 15% are satisfied with their real human life expectancy of 80 to 100 years.

No doubt, religious factors also have an impact on the different opinions regarding immortality. Most religions assign ►God a monopoly on being immortal; humans can at most aspire to having one part of themselves, the soul, attain immortality, at the cost of the body's perishing. However, we should not think that in the long run we even have a choice. An effective remedy against aging would be the commercial success of the century, if not the millenium. Thus, at some point the immortality treatment, if it is indeed possible, will be commercially available. The Hippocratic oath, if left unamended, would at that point favor using this treatment even if its use contributed to massive social inequality or overpopulation.

To be sure, an immortal society would be very different from present-day society. Reproduction would have to be regulated by law, as it already is in China. Children would become a very rare and spectacular phenomenon. Schools would close down; universities would transform themselves so as to focus on enabling immortals to spend their lives in the most meaningful way — lifelong learning. Pensions and retirement plans would be abolished. But a lot of tension and stress would also disappear from our lives, as immortals would presumably take a lot more time to make decisions and tend to put things off indefinitely.

An interesting argument against the desirability of immortality has been put forward by the philosopher Bernard Williams in an article called "The Makropoulos Case" (the title comes from a play by Karl Capek about an immortal woman). Williams's argument is subtle and complex, but its main points amount to, basically, these: Either there is a limit to how much change you can undergo in an infinite life, or there is no such limit. If there is such a limit, then, in time, the things you experience will seem increasingly just to be repetitions of things you've already experienced. Over an infinite time span, your life would become, for you, a maddeningly repetitive and tedious affair with nothing but more repetition to look forward to. At some point, Williams argues, anyone would simply — like Emily Makropoulos in the play — want out. If, on the other hand, there is limit to the change you undergo, then, again over infinity, the being you will eventually become has so little in common with you now that you now could have no motive to want that being to exist. Either way, the infinite prolongation of one's existence — either here or in some more ethereal realm — cannot, Williams argues, be considered desirable once its implications are thought through. (This, of course, does not undermine the reasons we might have to want a considerably longer existence than the one we can now anticipate.)

Three Routes to Immortality

The obvious question remains of what your own particular prospects of becoming biologically immortal are. The technologies mentioned above are still in their fledgling stages and are, in comparison to military arms research, hopelessly underfunded or even politically inopportune due to the fact that they are based on genetic engineering. Nonetheless, there are ways you can at least increase your immortality prospects. Depending on whether you are a passive or active, a religiously- or a scientifically-minded person, you might take any of these three routes to the goal of prolonging your life indefinitely or even infinitely:

![]() The

many-worlds route. Don't do anything, for you are already (almost) immortal.

According to Everett's ►many-world interpretation of quantum theory, the world splits up into several world branches with each quantum event. If you die within one branch of the event and live in the others, your consciousness will automatically decide in favor of the latter, since the former would have no place for it. Thus, from your own point of view you can die only at the point at which all branches of a quantum event end with your death — if the world were destroyed by a comet, for example. Otherwise, you can eat, drink, smoke, and live a life as risky as you like without thereby reducing your life expectancy.

To be sure, Everett's theory does not protect you from the unpleasant side-effects of such a life-style. There is one other drawback to counting on this strategy: The majority of scientists do not think very highly of the many-worlds interpretation.

The

many-worlds route. Don't do anything, for you are already (almost) immortal.

According to Everett's ►many-world interpretation of quantum theory, the world splits up into several world branches with each quantum event. If you die within one branch of the event and live in the others, your consciousness will automatically decide in favor of the latter, since the former would have no place for it. Thus, from your own point of view you can die only at the point at which all branches of a quantum event end with your death — if the world were destroyed by a comet, for example. Otherwise, you can eat, drink, smoke, and live a life as risky as you like without thereby reducing your life expectancy.

To be sure, Everett's theory does not protect you from the unpleasant side-effects of such a life-style. There is one other drawback to counting on this strategy: The majority of scientists do not think very highly of the many-worlds interpretation.

![]() The

religious route. This is based on the assumption that a very large group of people cannot err. Become a member of a popular religious community that holds a firm belief in an eternal life after death. ►Islam, for example, can teach you some concrete and in fact — at least for heterosexual male followers — quite ►pleasant details regarding this topic. The size of the community of followers, as well as their ability to believe firmly and deeply in their religion and their respective god(s), can also be important. Therefore, select a religion that suits you — one that you can really throw yourself into. Otherwise, do as much good during your life as possible, since in most religions this will help you improve your status with regard to eternal life.

The

religious route. This is based on the assumption that a very large group of people cannot err. Become a member of a popular religious community that holds a firm belief in an eternal life after death. ►Islam, for example, can teach you some concrete and in fact — at least for heterosexual male followers — quite ►pleasant details regarding this topic. The size of the community of followers, as well as their ability to believe firmly and deeply in their religion and their respective god(s), can also be important. Therefore, select a religion that suits you — one that you can really throw yourself into. Otherwise, do as much good during your life as possible, since in most religions this will help you improve your status with regard to eternal life.

![]() The ►cryonics approach, based on the assumption of unlimited technological progress. First, travel to the ►land of unlimited possibilities (the only place where this route is open to you). Second, purchase a life insurance over $30,000. Then get in touch with a cryonics institute (you'll find a list of addresses

at ►www.cryonicssociety.org). Bequeath your life insurance to the institute in return for their low-temperature preservation of your body immediately after your death. Even if you select this route to immortality, you should still strive to do a lot of good deeds during your lifetime and make sure others know about it. That will increase the chances of future generations' bearing the costs of defrosting and reviving your body.

The ►cryonics approach, based on the assumption of unlimited technological progress. First, travel to the ►land of unlimited possibilities (the only place where this route is open to you). Second, purchase a life insurance over $30,000. Then get in touch with a cryonics institute (you'll find a list of addresses

at ►www.cryonicssociety.org). Bequeath your life insurance to the institute in return for their low-temperature preservation of your body immediately after your death. Even if you select this route to immortality, you should still strive to do a lot of good deeds during your lifetime and make sure others know about it. That will increase the chances of future generations' bearing the costs of defrosting and reviving your body.

* Ebert and Southon, Confirmation of longevity for Strongylocentrotus franciscanus with 14carbon, Fishery Bulletin 101(4), 2003

Links Related to the Topic

■ Poll: When do you want to die?

■ Methuselah Foundation

■ Project Immortality

■ Reversal of the Aging Process

■ Commercial Immortalism

■ Society

for Immortalism