Soul (from Old English sawol and other Germanic cognates such as Old High German seula, "belonging to the sea"): traditionally regarded as the ►eternal and ►immortal part of a human person.

Philosophers such as Plato and Thomas Aquinas, as well as most religions, teach that the soul is immortal, albeit on the basis of widely varying reasons. In Western philosophy the soul has been traditionally conceived of as an indestructible, indivisible substance or idea — perhaps even, per Leibniz, as a ►monad — and consequently as something that cannot decay. Religions sometimes assert the immortality of the soul on the basis of an argument from divine justice: the soul is supposed to receive in the hereafter or at reincarnation the reward or punishment for the acts of the respective person. But what is the soul in the first place? It may be frequently identified with the consciousness, will, character, conscience, and/or memory of human beings (though it is important to point out that one can believe in the existence of any or all of these things without believing in the sorts of non-material, indestructible entities that souls are traditionally understood to be). This raises the question whether a) animals and b) machines, too, can have a soul — or even just (!) consciousness.

As every dog owner knows, the behavior of higher animals does also suggest the presence of will, character, memory, and even from time to time guilty conscience. And we could program a computer in such a way that it behaves in accordance with these characteristics. It seems more difficult to answer the question about consciousness, for consciousness is generally viewed as involving the ability to become aware of oneself as a thinking being (though philosophers may distinguish more carefully between consciousness and self-consciousness — awareness and awareness of oneself, respectively). To be sure, it has been demonstrated, by painting colored paints onto their foreheads, that monkeys and even elephants are able to recognize themselves in a mirror. But this doesn't necessarily mean that they have (self-)consciousness, since the latter commonly is not defined by external behavior but by an inner experience of which the behavior is at most a manifestation.

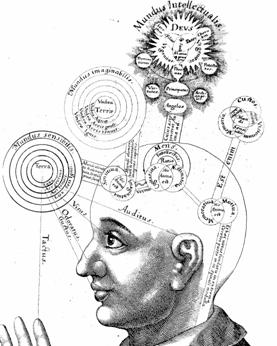

Components of Consciousness (Robert Fludd, Spirit and Consciousness)

Whether a natural or artificial creature has consciousness cannot be verified beyond all reasonable doubt by observation alone. Even in human beings, with the possible exception of our own case, it seems impossible to establish the presence of consciousness — let alone a soul — with absolute certainty. It seems that at most we can directly experience consciousness only in ourselves and infer that others similar in their behavior to us also have it; but this inference is anything but certain.

Why do we experience something when certain neuronal processes occur in our brain? Or are we rather just like machines reacting to stimuli, while our consciousness is but an illusion? (The person who entertains this second question may wish to ask him or herself how we can make sense of an illusion as anything but a certain kind of conscious experience in the first place.) But could a mere stimulus-response mechanism produce such complex actions as ours in the first place? And perhaps more critically, even if it could, isn't the experience of consciousness something separable from any such mechanism and its resultant actions? At least two empirical methods of exploring these questions have been proposed. First, we could try to ever increase our understanding of the neuronal processes in our brain. Second, we could simulate a sufficiently complex brain in a sufficiently powerful computer and then see whether consciousness is generated — or at least something that looks like consciousness "from the outside".

Souls in a Computer?

Machines are able to speak with human voices, recognize people by their faces, and overcome obstacles to reach a certain goal. They can play, learn, and reprogram themselves. But can they be conscious? Can they develop a soul? At this point, artificial intelligence is not yet sufficiently developed to answer this question. The hardware of a human brain alone is still far superior to any machine. We can today accommodate one million transistors per square millimeter in a computer chip, yet our cortex contains 100 million synapses per cubic millimeter. Overall the human brain possesses a computing power of 1016 three-dimensionally interconnected synapses — a hundred million times more than a state-of-the-art microprocessor with its approximately 108 switching elements, which are but two-dimensionally interconnected. Nonetheless, computers will no doubt reach and even exceed the computing capacity of the human brain at some point within the next 30 years. Then the matter will get interesting (►Singularity).

The Turing Test, which was proposed more than 50 years ago by the mathematician Alan Turing, defines artificial intelligence as a conversational aptitude. If in a conversation with a computer we cannot distinguish the computer's answers from the answers of a human being then the computer is ascribed intelligent consciousness. To be sure, many contemporary pieces of software, such as the smartphone assistants Siri, Cortana, or GoogleNow, can conduct conversations. Unfortunately they all are still far from reaching the level of intelligence required by the Turing test:

JCL: Hello, Alice.

ALICE: Hi there.

JCL: Do you know an alternative proof of Goedel's incompleteness theorem?

ALICE: No. Not a robot. Probably a human. Maybe a celebrity? That's not something I get asked all the time.

JCL: What do you know then?

ALICE: I tend to know a great deal. Tell me what subjects interest you.

JCL: Anything about infinity.

ALICE: I can't think of anything. You think of something.

JCL: Hmm.

ALICE: Studies show that 99% of people spell Hmm with 2 M's.

To distinguish genuine consciousness from merely simulated consciousness we may need to ask our computer the right questions. These could be the same questions that stood at the beginning of human reflective awareness (and also at the beginning of this dictionary): Does space have a limit somewhere? Does time have a beginning and an end? Where were we before we were born? Whence do we go after death? But even if the machine is able to behave externally just like a human being and gives answers that sound proper, does that already establish that it has a soul (or even a consciousness)? And if not, what is missing? There are different answers to this question corresponding to different philosophical positions on the nature of consciousness and/or the soul:

![]() Idealism: All that exist are mental, that is, non-material entities (essentially, minds or souls and their states). The challenge is not to account for such things, but rather to explain how what we think of as merely material entities — like the computer in the example — are, in some way, mental ones (if not minds themselves, then products or states of our minds).

Idealism: All that exist are mental, that is, non-material entities (essentially, minds or souls and their states). The challenge is not to account for such things, but rather to explain how what we think of as merely material entities — like the computer in the example — are, in some way, mental ones (if not minds themselves, then products or states of our minds).

![]() Dualism:

Conscious minds, or souls, are private, non-material entities that interact with material ones such as human bodies. No mere machine (or other material entity), regardless of how effective it is at replicating the behavior of a mind- or soul-possessing being, is one.

Dualism:

Conscious minds, or souls, are private, non-material entities that interact with material ones such as human bodies. No mere machine (or other material entity), regardless of how effective it is at replicating the behavior of a mind- or soul-possessing being, is one.

![]() Materialism:

All that exist are material entities. If minds or souls are conceived of as non-material, there are no such things. Since, however, there seem to be some important differences between what we consider beings with minds and what we consider beings without them, it seems more plausible to say that minds (at least) exist, but are material in nature.

Materialism:

All that exist are material entities. If minds or souls are conceived of as non-material, there are no such things. Since, however, there seem to be some important differences between what we consider beings with minds and what we consider beings without them, it seems more plausible to say that minds (at least) exist, but are material in nature.

Under the heading of materialism fall several positions:

![]() Behaviorism:

Minds (or souls, if you will) are nothing but complex dispositions to behave. (In philosopher Gilbert Ryle's famous phrase, the notion of a private, inner, non-material consciousness or soul should be dismissed as the myth of the "ghost in the machine".)

Behaviorism:

Minds (or souls, if you will) are nothing but complex dispositions to behave. (In philosopher Gilbert Ryle's famous phrase, the notion of a private, inner, non-material consciousness or soul should be dismissed as the myth of the "ghost in the machine".)

![]() Mind-brain identity theories: Conscious states are nothing but highly complex neuronal states of physical brains — the actual gray matter that humans and other animals carry around in their skulls.

Mind-brain identity theories: Conscious states are nothing but highly complex neuronal states of physical brains — the actual gray matter that humans and other animals carry around in their skulls.

![]() Functionalism: All mental states, including conscious ones, are functional states similar in kind to the states of a computer program. As such, they can be implemented in various kinds of hardware — wet gray stuff in our case, silicon chips in the computers. It follows that a computer that is functionally identical to a human — one that passes the Turing test, in essence — possesses the same mental states; there is nothing else to having those states, nothing else to being conscious.

Functionalism: All mental states, including conscious ones, are functional states similar in kind to the states of a computer program. As such, they can be implemented in various kinds of hardware — wet gray stuff in our case, silicon chips in the computers. It follows that a computer that is functionally identical to a human — one that passes the Turing test, in essence — possesses the same mental states; there is nothing else to having those states, nothing else to being conscious.

Finally, there are what may be considered the two most extreme positions on this issue, occupying as it were opposite ends of the spectrum of possibilities:

![]() Eliminative materialism: minds, mental states, conscious states, etc., are all hypothetical entities postulated by an informal theory that we may term "folk psychology". As such, we only have reason to take such things seriously to the extent that we have reason to take the theory seriously. However, folk psychology is a very flawed theory whose credentials are no better than those of, say, folk physics. Hence we should simply dispense with all talk about such things; they have no place in a properly rigorous scientific theory of the human being (or of anything else).

Eliminative materialism: minds, mental states, conscious states, etc., are all hypothetical entities postulated by an informal theory that we may term "folk psychology". As such, we only have reason to take such things seriously to the extent that we have reason to take the theory seriously. However, folk psychology is a very flawed theory whose credentials are no better than those of, say, folk physics. Hence we should simply dispense with all talk about such things; they have no place in a properly rigorous scientific theory of the human being (or of anything else).

![]() Mysticism/pan-psychism:

Everything in the universe has a soul or is part of one all-embracing cosmic soul.

Mysticism/pan-psychism:

Everything in the universe has a soul or is part of one all-embracing cosmic soul.

For many philosophers the question of the nature of soul and consciousness constitutes the upper limit to our drive to knowledge. There is, however, one comfort: even if human intelligence does not suffice to find a definitive answer to this question, we may at some point be able to have a computer tackle it.

Links Related to the Topic